Lightyear CEO Martin Sokk: We Monitor Marketing ROI Extremely Carefully

- catlinpuhkan

- Sep 29, 2025

- 12 min read

Lightyear is a financial/investment platform operating in 25 countries, in which Richard Branson has also invested. In the summer of 2025, Lightyear raised 23 million dollars for expansion.

Very generally, the start-up world is divided in two. Some put all the emphasis on the product, with the philosophy: "a good product sells itself." Others have more faith in marketing and sales, the market is more competitive or the product is not as distinctive, so more steam is put into classic marketing and sales. Where do you stand on this scale?

I think it's a scale, not a black-and-white worldview. But we have a pretty strong belief in the product. If the products are all the same, you have to do more marketing to stand out. If it's possible to make a genuinely better and distinctive product, you should do it.

Example: most of the money in Europe sits in banks. Banks' focus is on loans – they haven't developed investment products for decades. Banks' investment products are essentially all the same, the brands differ, the prices are more or less similar. When we enter the market, we can offer a 10 times better service at a 10 times better price. Accessibility, pricing, and use – a completely different league. So where do we put our money?

Primarily into making that difference even bigger. With a good product, people will start talking about it, "word of mouth" is the best marketing.

In the financial sector, trust is crucial, especially when entering a new market. It's easier to create awareness and trust in Estonia, but in a new market, nobody knows anything about you. I'll give you an example: if a Bulgarian platform came to Estonia, one I've never heard of – would I dare to give them my money? How do you build trust?

Trust doesn't happen overnight. Especially in finance, you have to do a lot of things right. First: the regulatory base, everything according to the law and done very well. If there are no problems, this provides the foundation for trust to develop.

Second: what kind of products you build. The barrier of trust varies by product. In "get-rich-quick" type products, trust works differently – their customers' number one interest is "can we make a lot of money quickly". We are at the other end: we want a platform where people make sensible decisions and invest long-term. This type of client thinks about trust differently; "get-rich" talk kills trust. We have to create common sense products: statistically logical, used worldwide, and do it transparently.

But how do you communicate that? Trust has to be established relatively quickly. Psychology theories say it's a spinal-cord-level thing. Whether you trust a person immediately or not; whether you run away or interact with them.

Those primal feelings are real, but if your product is logical to a person and you can explain it, that's the foundation. Another aspect: trust doesn't happen all at once. It is often said that you have to see a company seven times before you start doing business with them. It takes time. In product communication, what's important is: on what values is the product created; what you see on the homepage – do you promise "get rich quick" or do you show a "sensible way to invest". Our argument is that we bring the costs down and explain how.

Everything takes time: I have an experience where we sponsored an event; I was on stage, talking about the product, wearing branded clothes. At the end of the event, a person came up to ask: "Who are you?". I said I was from Lightyear. He said: "Never heard of it, what do you do?". We talked, and despite my presentation, the message still didn't get through to him. He was even wearing socks he got from our booth!

This shows that sometimes it takes a very long time for you to even "see" a company. One element of trust is time. When you see that people are doing things right and for the long term, trust develops. Even better, if your friends or people you consider sensible use the product - trust increases.

Start-ups use foreign capital, investors want quick results; at the same time, building trust takes time. How do you solve this dilemma?

It's a bit different across start-ups. For us, a start-up in a regulated world, the problem is that you can't do anything overnight. Just getting a license takes about 12 months. A typical start-up operates on a 12–18 month horizon; we don't have that option. We know our things will take a year or so longer. But in product development, speed is also very important in our sector.

Example: we were in Hungary last year. Three client meetings in the morning, an event with about 100 participants in the evening. In the morning, we took the product apart, got a lot of feedback. One piece of feedback: notifications for tax accounts are missing. In the time between the morning and the evening event, we built the solution and put it live. The clients could already use it in the evening. This is a big deal for the client: we do what they want.

This gives us an advantage over traditional banks. Banks have a legacy; but in my opinion, that's no excuse. Banks are financial companies that use technology. We are a technology company that operates in the financial world. The way you solve things, the organizational structure, etc., is different. Our focus is very clearly on building investment products. We leave the rest of the financial world aside and we don't deal with it.

Lightyear client event in Hungary

You have many markets and plan to expand further. How standardizable is the go-to-market strategy? Can you go everywhere with one model, or does each market require a separate approach and budget?

In broad strokes, the approach can be similar, but every country is a little different. One common mistake: a good product is built in the US, and it's assumed that the UK is like a US state. They go and they fail, because a product that is good in the US doesn't work in the UK. The business model might even be illegal; taxes are different; the currency is different. The US company hasn't thought that it should support other currencies at all. So a separate solution has to be built for the UK. The dilemma: the US has 300+ million people; the UK has ~60 million. You have to invest a lot of resources for a smaller market, and often it's not worth it.

We thought about it the other way around: from the beginning, we make our product for Europe. Everything is built so that we operate in every country. The first thing we did was to enable multiple currencies, because currency exchange must work well. We know that every country has its own tax system; we made the system flexible for this. The languages are different, the stock exchanges are different, we built diversity in.

We also immediately got a license that allows us to go to many countries. We built the platform to be pan-European from the very beginning, we obtained the corresponding licenses. Once the foundation (license, currency, etc.) is in place, the actual market entry begins. The differences between countries are large; even just Southern Europeans vs. Germans, their attitude towards money can differ.

We don't choose markets like "Hungary is nice, let's go". Before entering a market, there are certain prerequisites: we have already opened the product for people to try. People start using it through friends' recommendations. We get customers from different countries - early adopters who have seen us in the media (e.g., Bloomberg, etc.). If we have even a few clients, we talk to them and try to understand if the product works.

Back to the "product vs. marketing" question: we go first with the product – we find out if it is sensible and good in the given market. We take the first marketing steps, for example, press coverage or a small paid marketing campaign, to see where interest arises and the first users appear. We can see if people are happy with the product, if they want additional features, if they stay on as users. If we see that it works (Hungary was a good example), only then do we really enter the market.

Market entry generally goes like this: we meet with the local start-up community, we hold an event, we introduce the product. Then we arrange media coverage, we get more users from whom we can get market-specific feedback. Then we build out local language support, customer communication, tax accounts, other localizations – and then we open up forcefully. Then we can also communicate forcefully: "We have made these things specifically for Hungary."

What do you do to get early test users?

We initially do PR and test the markets with advertising in paid channels. A Facebook ad is easy to do, but in our world, it doesn't work very well because the cost per click is high. We have a long-term service; the fee from the client is small and comes in slowly over time. It's not sensible to pay a large sum for "dubious clicks". But it is still one way to open the door a little and see if anything is happening. Press coverage also helps.

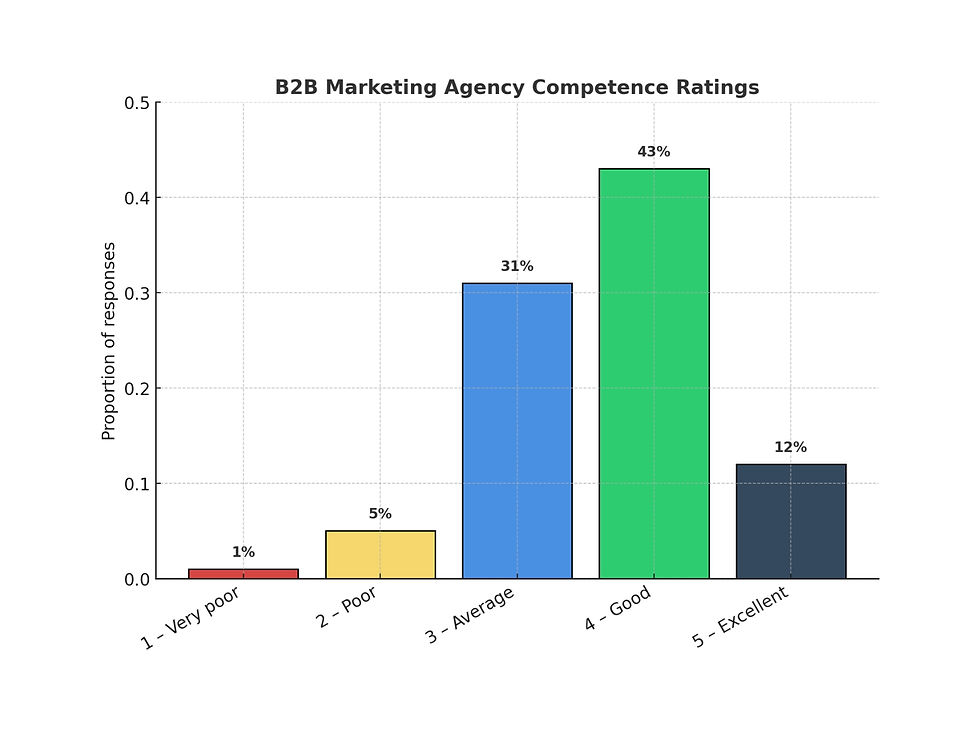

The lion's share of growth (about 60%) comes from referral programs and organic channels.

If, for example, a Bulgarian company sends a press release to the editors of Äripäev or Delfi – the probability is that it will be redirected to the advertising department. How do you manage to get press coverage?

Use the opportunities and advantages you have! For example, in Hungary, people like the Estonian start-up world. The image of an Estonian start-up works in our favor. Wise has had an office there – this has contributed to Estonia's recognition. We say: "We are an Estonian start-up," "We have a background from Wise," "Richard Branson has invested in us," and these arguments work well in terms of building recognition.

Then you work further with local people, convince them that we are not just "some random thing," but something interesting to write about. You go and tell your stories.

How important is a "local face"? Does each country need its own representative, or do you go as a foreigner?

You can get the first part done as a foreigner, but you can't build growth as a foreigner. At some point, the ability to connect with the client disappears if you don't speak the local language. The bigger the country, the more important it is to speak the local language. We have people in every target country who speak the language and can explain who we are. We have recruited strong people from many countries.

As a CEO, what are the most important marketing metrics for you, by which you judge whether the team is operating successfully?

One of the main ones is profitability, ROI: every cent we spend needs to be earned back. We look at this by channel: press, partners, paid marketing, referral, etc. In addition, LTV and CAC. We have a good overview of the profitability of clients coming from each channel; based on that, we decide where to spend more money.

We do this in great detail – each country separately. We also monitor in almost real-time: if we do an event today – will people start using our product after it? I often have a dashboard open; sometimes I see that many Estonians or Germans started using the service; then we correlate events and try to understand why right now.

For us, registering a new account is less important than the user also putting money into the account. In marketing, you shouldn't immediately put millions into one campaign. I first do the smallest thing; if it works, I escalate. I don't have such good intuition to predict what will work. I open the database: in this country, the conversion is like this, in another it's different – we scale the things that work.

How important is the founder's role as an influencer? How important do you consider it to be visible on social media?

It's quite important. I represent the company; I don't have a "personal" social media – all channels are under my name, but the content is purely about Lightyear topics. Sometimes I also post pictures of dogs – we have many dogs in the office and they are always doing some silly things. Sometimes there's a picture of a dog sleeping in a pile of Lightyear logos, that was the most viral post on LinkedIn so far.

Showing the human side is important. In addition, we talk about how we plan, launch, etc., but alongside that, we also show the enjoyable daily life.

What has been the most difficult market you have entered?

The larger the market, the more difficult. In smaller markets, minor shortcomings are sometimes forgiven, but in larger markets, they are not. In our world, Germany is the market with the strongest competition – most developed, local competitors, local regulators, local language and founders. To bring growth from there means you have to enter with a much better product than the competitors. That is difficult.

We are growing in Germany, but we don't invest too much there. Why? Because today we don't have a big advantage there compared to the locals. The other 300 million Europeans are easier to serve. Hungary is 10× smaller than Germany and there is less money there, but we are still talking about billions that have been neglected – I'll go and build there. The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain – there isn't such strong competition there either. Once I get the product to a point where I am better than others in Germany too – then I will invest more there.

Lightyear UK client event

If you could go back in time: what are the lessons from marketing/PR/communication? What went well and what would you do differently?

Starting with the good things: it's worth thinking globally. An effort that doesn't seem relevant today can bring a lot of benefit in the future. For example, we convinced Richard Branson to invest. We worked hard and the result: no matter which country we go to, it is often said "you are that Branson investment". Such a big name that it's hard to compete with – it's worth the effort.

What went wrong: in the beginning, I didn't understand well what marketing cost means. That was painful. If you can't measure, it would be better not to do marketing and save the money. Otherwise, you get a "good feeling" for a moment that many people are reacting, but if you don't understand who they are, why they are here, and how much value they create, it may happen that they didn't come to use the product. Then they get disappointed, create a bad vibe, you lose the client and the money. Measurement is very important.

The question is not "can we get clients," but "how to get the right clients". The wrong clients do harm, even if they generate a little revenue. If you build the company through clients (like we do), you read all the feedback, improve the product and pricing based on them – then the wrong client leads to the wrong decisions and you build the wrong product.

In the beginning, we had a very small product and we went for too broad a client base; they brought ideas that were not necessary for us. Luckily, we realized it quickly and focused on the clients we needed and built the product of today.

How precisely is your ICP (ideal customer profile) defined?

Quite precisely, but there are many nuances. We don't just monitor who the client is, but also what they do exactly: how long they are in our environment, what transactions they make, why they make them, what is important to them. Our client is a person who wants to grow money long-term.

Give one recommendation – a podcast, blog, book, etc., that has recently impressed you?

Read the autobiographies of big business names. They are not usually strategic business management manuals, but they describe very well what you have to do. For example, Phil Knight's "Shoe Dog".

Lightyear's Go-to-Market Strategy

Phase 1: Product and Foundation

Create a Superior Product

Goal: Deliver “10× better service at a 10× better price” than competitors.

Build Foundational Trust

Ensure full compliance with all regulations to create a solid foundation for trust.

Use transparent pricing and position the product for sensible, long-term investors, avoiding a “get-rich-quick” narrative.

Design for Europe

Build the product from the start to be pan-European: multi-currency support, flexible tax accounting for different countries, multilingual capabilities, and access to multiple stock exchanges.

Phase 2: Initial Market Testing

Quietly Open for Early Adopters

Allow early users to join through recommendations and media mentions. Collect feedback to confirm product-market fit across different regions.

Test Markets with Small Campaigns

Run limited PR and paid campaigns. The key metric is not sign-ups, but deposits into accounts.

Leverage Natural Advantages

Use unique selling points to attract media interest, such as being a successful Estonian start-up or having Richard Branson as an investor.

Phase 3: Market Entry and Launch

“Soft Launch” with Community Engagement

Engage local start-up communities, host introductory events, and secure local media coverage.

Localize Before the “Hard Launch”

Adapt the product fully for the specific market with local language, customer service, tax reports, and legal compliance. Communicate clearly that the product was “made especially for [country].”

Prioritize Referral-Based Growth

Focus on referral programs and partnerships as primary growth channels. Use paid advertising cautiously, testing effectiveness before scaling.

Phase 4: Scaling and Growth

Establish a Local Presence

Build local teams who speak the language and connect with customers in each target market.

Focus on Easier Markets First

Scale where competitive barriers are lower and advantages are stronger. Delay entry into highly competitive markets (e.g., Germany) until the product clearly outperforms local offerings.

Measure Everything and Scale with Discipline

Start with small marketing experiments and scale only proven tactics.

Track ROI and performance rigorously, analyzing each market and channel separately for data-driven decisions.